The tradition of world time

It was the invention of the railway that obliged watchmakers and public authorities to standardise time zones. Prior to the locomotive, people only lived in real time, which indicated midday when the sun was at its highest. There were therefore as many local times as longitudes, but nobody realised the fact, given that one could only travel a few kilometres a day. With the train, progress dictated a new need to watchmaking. And this same progress, with the advent of the telegraph, provided the means of communicating the exact time over great distances. It was the hegemony of the merchant navy and the military in the 18th century that prompted the British court to offer a handsome reward to watchmaker John Harrison. His watch, now exhibited at the Greenwich Observatory, was exact enough to measure longitudes by providing the ship with the local time in its port of origin so that it could be compared with the actual time. Before this, sailors had no idea of their latitude. Incapable of working out their location with any degree of precision, they lived in constant fear of missing their target.

Under the influence of geographers, this time, the same 18th century saw the birth of world time watches, like the one built in 1705 by Zacharias Landeck, exhibited at the Musée International d’Horlogerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds. These were the origins of iconic watches like the World Time model by Vacheron Constantin, or in a more playful fashion, the WW.TC by Girard-Perregaux, of which the men’s version indicates the local time in various stock exchanges, while its ladies’ version displays that of the world’s main shopping streets.

From Newton to Breguet

Physics have also always found in horology an indispensable bridge between theory and practical applications. There is not a single discovery, nor a single formulation that has not been implemented in this field. In 1684, when Isaac Newton wrote to Edmund Halley to tell him of his theory of universal gravity, he unwittingly raised a problem for horology – the influence of this same gravity on pocket watches – that Abraham-Louis Breguet would resolve a century later with his tourbillon, which today remains one of the most iconic complications in the entire watch industry.

In the same way, when renaissance scientists worked on the dilation of metals in relation to temperature, they paved the way for a new generation of clocks. The master-watchmakers then created composite pendulums, with rods made of different metals – some grey, some gilded, which react differently to heat, self-compensating for their deformations in such a way that the in the end the length of the object is the same.

After the Big Bang

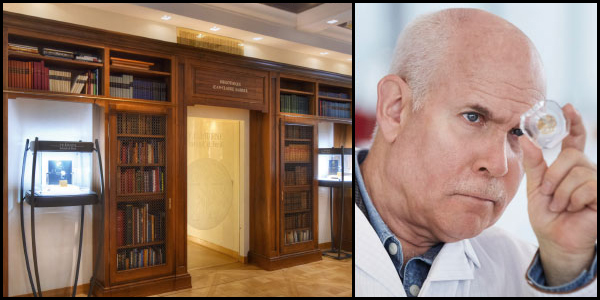

Hublot, which has just announced the creation of Magic Gold, a new scratchproof 18-carat gold, is in fact pursuing this age-old tradition of identifying the weaknesses of a material – dilation for clocks, lack of longevity for gold – and resolving them with the help of scientists. For Hublot, it was scientists from the EPFL (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne) who found the solution, by injecting pressurised molten gold into a type of ceramic sponge until it was completely filled. Science and horology: the fruits of this exchange are tangible when they improve the precision, reliability or lifespan of a timepiece; or simply poetic, when they allow watches to display within a 40 millimetre diameter space that which the universe engraves across the whole sky.

As specialised watchmaking historian Dominque Fléchon reminds us, history is above all the child of astronomy, and the designers of the great brands still remember this, when they offer the Paris sky on a dial, as Van Cleef & Arpels first did in 2008; or astronomical complications signed Ludwig Oechslin for Ulysse Nardin; or ecliptic variations engraved on mobile bezels. Basically, like the other sciences, watchmaking swings between allegory and a description of the world. Between practical applications and serving as the ostentatious attribute of power. In China, over the millennia, the measuring of time was an imperial prerogative. This was both its good fortune, since exceptional means enabled horologers to achieve unprecedented precision; and its downfall, because its imperial stature meant it could not be popularised and used by both the emperor and his subjects. By way of contrast, in the south of France, the largest stone in one particular astronomical observatory simply indicates September 8, the date on which shepherds and their herds come back down to the valley.